What is a Place?

In 1974, Georges Perec sat in Paris' 6th arrondissement, meticulously noting the ordinary life in Place Saint-Sulpice, revealing the unseen "infra-ordinary" that shapes a place's essence. Fernwayer Editor Angelo Zinna provides his take.

[Photo: Angelo Zinna discovering that motion amplifies the essence of a place.]

What is the space that surrounds us? George Perec obsessed over this question in his 1974 Species of Spaces and Other Pieces

What is the space that surrounds us? George Perec obsessed over this question in his 1974 Species of Spaces and Other PiecesOn an autumn day of 1974, French author Georges Perec decided to invest a few days in trying to put down on paper an entire neighborhood in Paris’ 6th arrondissement. Sitting at a café in Place Saint-Sulpice, steps away from the Jardin du Luxembourg, Perec’s set himself up for an impossible endeavor – to provide a sense of place by describing all that was happening in the present moment, to track down common things, to draw the contours of what usually goes unnoticed.

After two hours of working on the project, Perec came to the realization that capturing the “infra-ordinary,” as he called all that happens when nothing happens, could quickly become too much to handle. Place Saint-Sulpice was – and continues to be – not just architecture, cafes, shops and parking lots but “tens, hundreds of simultaneous actions, micro-events, each one of which necessitates postures, movements, specific expenditures of energy”. Nevertheless, the writer continued to compile the inventory of An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris from his observation decks at Tabac Saint-Sulpice and Café de la Mairie.

The question of what defines a place is one I’ve kept encountering over the years, both inside and outside of travel literature. There is geography, the features of our surroundings that we can see and touch. And there is history, the set of events that have contributed to the formation of cities and communities. Yet, as Perec and many other authors, photographers and artists have suggested in the past, there is something else that escapes this intersection of space and time. Something less firm and more difficult to point our finger at – an ever-transforming universe of daily habits, interactions, words spoken and coincidences happening that allows us to feel a place even when we don’t know what a place actually is.

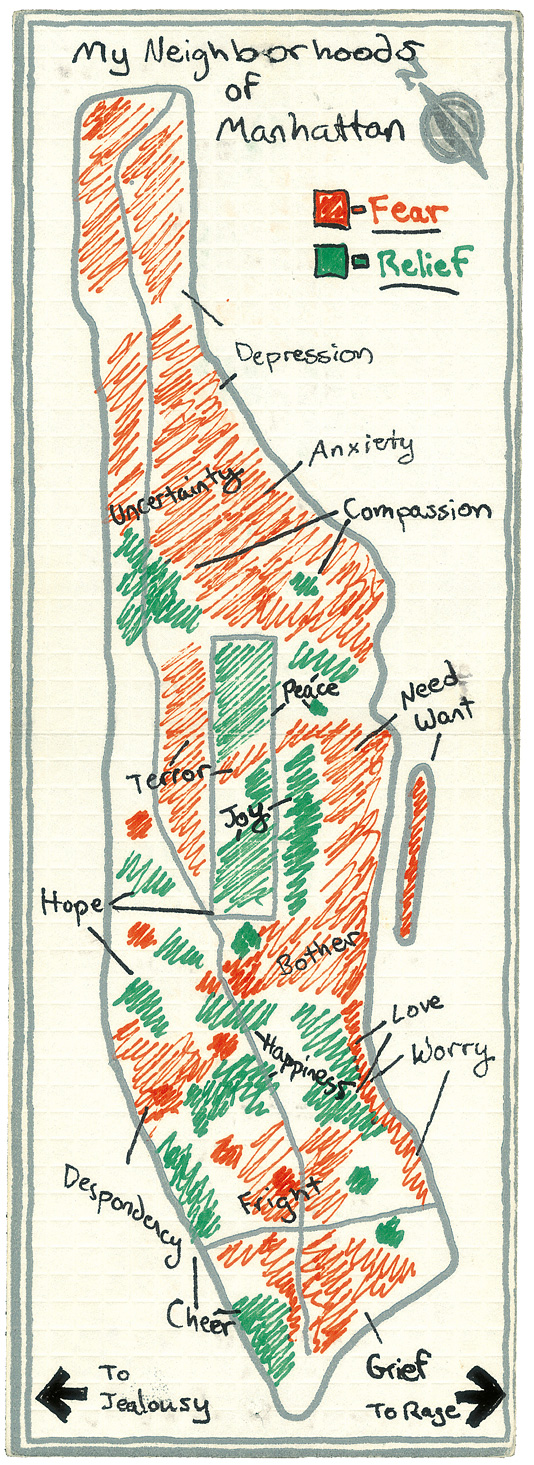

An emotional map of fear and relief zones from Becky Cooper’s Mapping Manhattan.

An emotional map of fear and relief zones from Becky Cooper’s Mapping Manhattan.Feelings complicate things, however. In her Mapping Manhattan project, Becky Cooper showed that a place can multiply endlessly when we take into account how individual people perceive it. In 2009, Cooper distributed a series of blank maps of Manhattan to the island’s residents, asking them to return it after drawing the elements that defined their mental picture of the city. What she received back was an incredibly varied collection of memories, dreams and routines. From the locations of romantic encounters to zones of fear and relief, Mapping Manhattan shows images of a space with fixed boundaries but infinite layers.

Physical places are easily mapped, but imagined places defy strict categories. Still, the first cannot exist without the latter and vice versa. As he moved forward with his descriptions, Perec’s clinical approach to defining a place seemed to clash with the “living” nature of Place Saint-Sulpice.

After three days and some fifty pages of text, Perec ended his experiment abruptly. “The pigeons are on the plaza. They all fly off at the same time. Four children. A dog. A little ray of sun. The 96. It is two o’clock.”

In considering what defines a place, it's impossible to overlook the central role that people play. Beyond geography and historical events, it is the presence, actions, and interactions of individuals that breathe life into a place, transforming it to reflect their values while adapting to its constraints. As he observed the myriad of simultaneous actions and micro-events unfolding around him, Perec couldn't help but recognize that by inhabiting the space, people renewed the place at every glance. From the bustling crowds at cafes to the children playing in the plaza, it was the human presence that gave the place its character.

Similarly, Becky Cooper's Mapping Manhattan project revealed the diverse perspectives of the city's residents, each adding their own layer of meaning to the urban landscape. Whether it was the memories of past encounters, the routines of daily life or the dreams of future aspirations, people's experiences added a new layer of meaning to the place. Each story, struggle and triumph becomes intertwined with the fabric of the place, leaving a mark that transcends geography.

In an age where infinitely scrollable must-do lists shape our itineraries and picture-perfect sights are pictures before they are sights, what is it that makes travel still worth the effort? Perhaps an answer is to be found in Perec’s failure, despite the melancholic conclusion – if a place can never be exhausted, an opportunity for discovery will always await travelers who take the time to observe closely, no matter how familiar a destination appears at first glance.

It is, then, with an invitation that I’d like to inaugurate Fernwayer’s Journal - to slow down and read between the lines, to pay attention to all that hides below the surface, to stay curious. To take notice of all that happens when nothing happens and be surprised by everything that a place can be. ||