Standing Tall: Catalonia’s Human Towers Between Community Spirit and Invented Traditions

Often associated with ancient folk traditions, Catalonia’s castells have gained mass popularity in recent decades.

In 2014, a New York Times headline declared “Catalonia’s Human Towers as a Metaphor for Independence.” In recent decades, the Catalan folk tradition castells (‘castles’ or human towers) has been heavily associated with catalanisme, the broad cultural form of Catalan identification deeply tied to the independence movement.

In many ways, not least in its demonstration of strength and communal energy, the castells are a perfect metaphor for a romantic nationalism usually related to the 19th century. However, in 18th-century Spain where this tradition was born, it is unlikely that the castells held this nationalistic significance. Nevertheless, being such a spectacle, it is no surprise that the tradition is a perennial topic for travel writers and photographers, and those wanting to find clues as to the supposed mysteries and specificities of Catalan culture.

Depending on size and other considerations, the form a castell takes can vary. Typically, what onlookers see is, at first, concentric rings of people, sometimes ten or more layers deep, arms laced over the shoulders of the person in front of them and their heads kept down, collectively push inwards, supporting a base of four castellers stood, arms interlocked, in a circle.

Shutterstock

Upon this base, or pinya (pinecone), a single ring of typically four people will grip each others’ biceps and stand, perched delicately on the shoulders of the inner core. On top of this ring another of the same number will climb and perch. This will be repeated until the team - the colles - reaches the limits of its ability.

To complete the demonstration, a child, usually a girl, called an enxaneta, will crawl up the entire structure, and, when they reach the peak of the tronc, the tower, stand straight for a brief moment to a round of applause before sliding down again.

From above, the breathtaking efforts of the catells such as the ones Tarragona is famous for, look like something born out of a psychedelic vision. The outstretched arms in combination with the pattern formed by the rising bodies looks like a moment of parallelism in a kaleidoscope. It mimics the twisting roots of a large tree: a structure hinting at natural forms; a gothic spire rising up from Catalonia’s past.

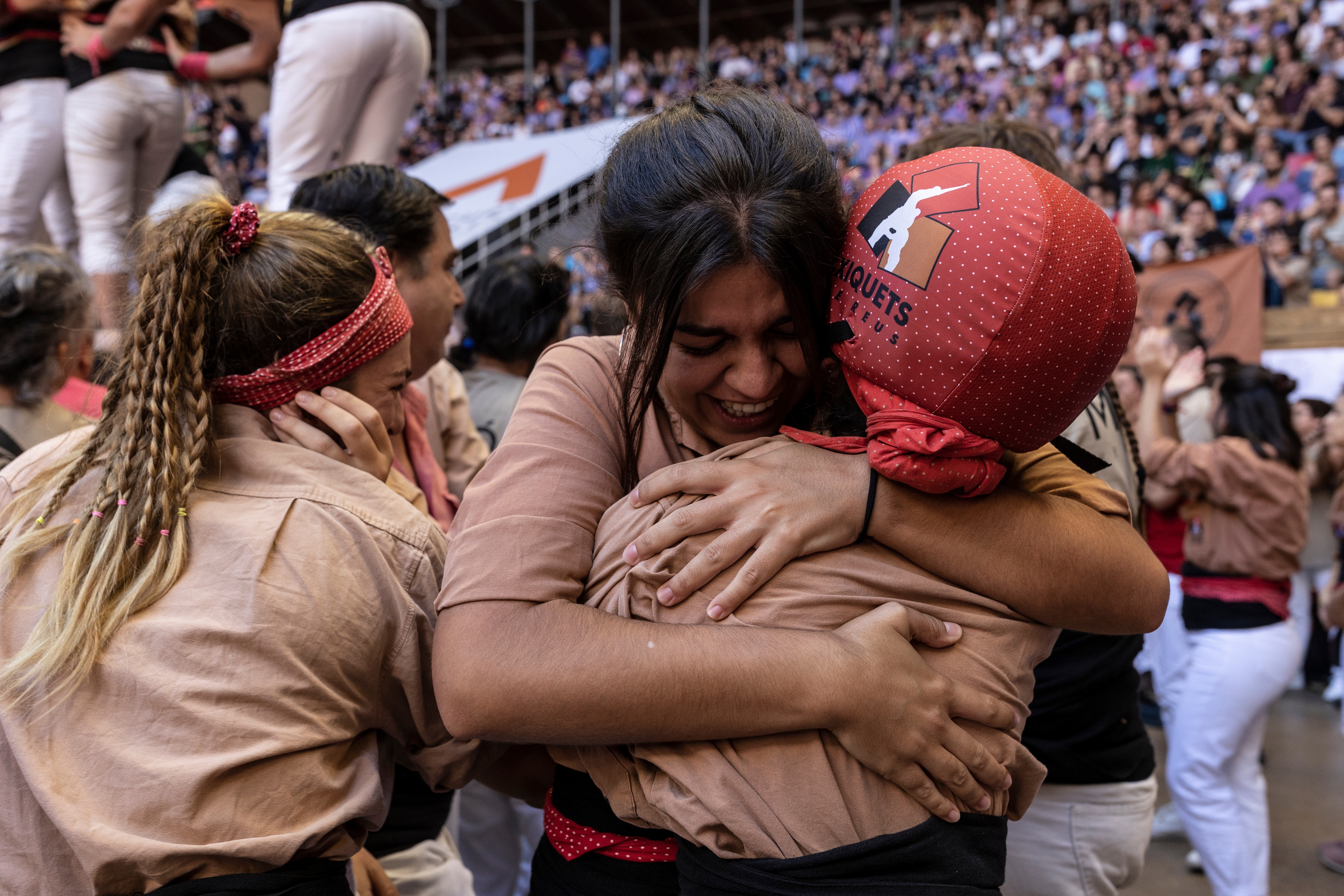

From the ground, what is most striking is the precariousness of the whole endeavor. The heart rate quickens as the enxaneta scuttles over many backs to reach the tower’s pinnacle. A successful castell – and there have been surprisingly few serious injuries or deaths recorded in recent history – is followed by a controlled deconstruction and much applause and hugging.

Coming across castells, by accident or on purpose, as I did in my neighborhood recently, reinforces the sense that Catalonia has a strong sense of civil society. It is a deeply community and family-oriented affair, kept alive by a dedicated community of practitioners. The towers are impressive no matter the size, and especially so when they’re kept in formation for the duration of an entire procession, as is typical in festivals from the Catholic tradition.

A small band playing traditional Catalan music was also present at the demonstration I attended. This music is played with grallas and flabiols, woodwind instruments, and a drum called tambori. There were members of the colles wearing T-shirts bearing the slogal “junts ho podem tot” (together we can do anything) – a good indicator of the social imagination the castells inspire.

David Ortega Baglietto

While castells likely developed from a dance tradition dating back around two hundred years, the ritual was also partially inspired by Muixeranga, a cultural practice from Valencia. This is not a region that today pictures itself as part of an independent Catalonia. The ritual appears pre-industrial – bold and folksy – but the tradition’s mass adoption as a regional identifier dates back only to the establishment of regional television a few decades ago.

Of course, the castells can be understood, for whoever wants it, as representative of a particular identity or nationality. Equally, before the 1980s, when women were first permitted to participate, they could have stood for male strength, and after that, as pointing towards the growing prominence of feminism in post-Franco politics.

Boban Vaiagich

It also started meaning something beyond a regional identity marker when UNESCO gave the practice protected status as intangible cultural heritage in 2010. At that point, it officially became part of the family of activities deemed important at the scale of all humanity. Undoubtedly, future communities with their own ideals will say it reflects whatever their aspirations are.

Even within the same timeframe, interpretations and significations change. As anthropologist Marian Vaczi wrote in 2016: “For conservative Catalans, they are an authentic folk practice and cultural heritage. For liberal urbanites, they satisfy their penchant for voluntary, democratic associational culture and vindicate urban space for communal use.” These two approaches aren’t necessarily always distinct in peoples’ minds.

What makes and will make such metaphors work is not the strength of the things that people say the castells represent. Rather, it is the castells themselves that hold power. This is because there is something inherently impressive, something that can’t be captured or described, about a mass of people making the effort to turn the body into a brick of a structure that reaches implausible heights. There is a collective, visceral magic to that moment when an enxaneta stands proudly atop a castell.

It is not only the inherent danger of the moment that makes it so engrossing. Actually, the audience doesn’t want the thing to fail, or for people to fall. We want it – them – to succeed. And it is this magic, this trust in the collective, that political agendas seek to emulate when they associate themselves with the tradition.

This inherent excitement about the action of making a human tower is perhaps why the practice can be found in a variety of societies, such as in China, India and Venice. It is also why they’ve become such a popular spectacle internationally, from being performed by the pyramids of Teotihuacan to being featured in a Travis Scott music video.

There is a slogan attached to the Catalan catells: “força, equilibri, valor i seny” – strength, balance, courage, and common sense. There is not much common sense in making a castell, but it takes a lot of sense to build a successful one. Dedication, balance, and precision are absolutely key.

The above description of a castell being built is actually a limited version of all the details and diversity involved in the art of the castellers. A ten-person-tall castell, for example (which is also the current record) is conceptually divided into five layers. The aforementioned pinya is not some random huddle of people but a foundational formation within which individuals are assigned key roles. Numerous types of structures can be built, some with troncs only one person thick, others having three troncs within one formation. The tradition of the castells is a tradition of human engineering.

Shutterstock

The uniform, inspired by traditional Catalan dress, is notable. The wide belt offers a double usage both as back support and as something to grip. The trousers are white allegedly because the first castells were made with the men wearing nothing below the belt but long white underwear. There is also the red handkerchief, often worn on the head and the colored shirts with emblems that refer to specific colles, similar to how football kits function. The football analogy extends weakly insofar as there has always been a competitive spirit between colles, and there are literal competitions between the teams.

Many teams aren’t all that old; the newest four were founded in 2019. This is a good reminder of what is referred to as invented tradition, the truth that much of what we take to be very old is surprisingly new.

The 19th-century journalist Juan Mañé Flaquer provides us with a historical example of how the castells were experienced and interpreted near the tradition’s inception (note that he was not an early adopter of catalanisme). Writing in 1853, he said that a castells competition in the town of Torredembarra demonstrated "heroic courage," an "expression of strength and suffering, which are the characteristic qualities of our countrymen." Additionally: "The castells absorb all the attention of neighbors and strangers” and that a “fight between two colles attracted an extraordinary influx of foreigners."

Shutterstock

The tradition plays a complicated and often paradoxical role in 21st-century Catalonia. It hints toward a historical record where there is mostly communal myth-making. It suggests some sort of pre-industrial Catalan consciousness (early practitioners were certainly mostly farmers and fishermen), but its boom has relied upon media technologies and urbanization. It has been useful for helping create a Catalan brand: for tourists, who seek supposed authenticity, and for Catalans who have sought to distance the region from Spain. Or, more specifically, the historical dominance of another castle – the Crown of Castile, considered the culturally dominant Spain.

There is now a museum dedicated to the tradition. It is located at Valls, home of the annual Decennial Candela Festival where castells are said to have originated. Text from the website claims that the museum wants to be “a communicating vessel” rooted in the neighborhood and the town, and also a home to “this human expression.” This is a perfect encapsulation of the push and pull between regionalism and folk universalism that is embedded in this story.

Castells is now part of the globalized world of cultural expressions. Considering the growth of colles over the past five decades, the tradition will likely continue to reinvent itself. Along the way, the sheer human force of the doing of them will continue to attract participants, journalists, and politicians who will each try to find in it some clue to the past, and what that means in the present.